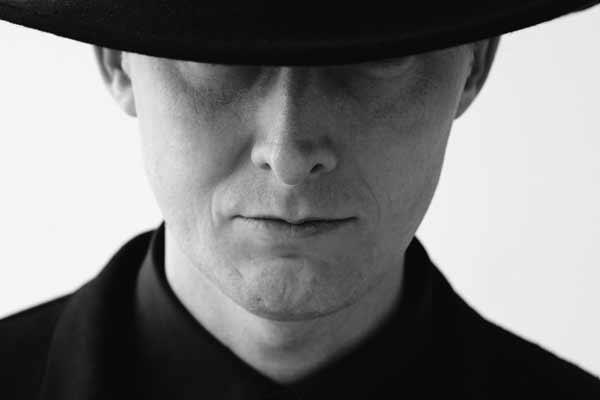

Brisbane composer, media artist and curator, Lawrence English released his newest album last month.

It's a record that explores themes surrounding the current world-political-social climate and how they make us feel.

Your new album, 'Cruel Optimism', is said to consider power both present and absent, and how it shapes the human conditions of obsession and fragility. What led you to create an album based on this premise?

The title of 'Cruel Optimism' is the name of a book written by the American critical theorist Lauren Berlant. I came across this book around the time I was working on my previous record, 'Wilderness Of Mirrors'. In her book, I found an incredible series of passages that, for me, suggested a means through which some of the key issues and conditions – that are so prevalent around us – could be critically examined.

The concept of cruel optimism for instance investigates why it is we struggle so much detaching ourselves from certain kinds of fantasy objects, such as the idea of the good life. These objects should bring us happiness, but in fact they erode the possibilities for happiness and actually function as barricades towards our fulfilment and contentment in life.

She argues that it is easier to keep the attachment that may destroy us, than remove that relational and through doing so seriously threaten the way it is we feel we can navigate our world. It’s a simple, but very powerful insight and I feel it has never had a greater societal relevance than at this moment.

The book also speaks to other issues and it was her writing around trauma, as an ever present state, rather than an exception and around that affect that I was particularly drawn to. The record is in some ways my unpacking of the perpetual state of unsettling and quite frankly abhorrent unfoldings we see around us.

In Australia, our government's treatment of refugees and asylum seekers for example is utterly inhumane. It represents a gross failing on our behalf as a nation and sadly these people are used as tools of political power.

Fundamentally, we need to remember underneath the discourse about this stuff are people, who are like you and like me. They dream, they breathe, they love and they grieve. To reduce them like we have is quite simply something I am repulsed and disappointed by.

Equally, we’ve seen continued gross failings of our indigenous people. Black deaths in custody continue and you need no other example of how serious this is than the recent video materials published of Ms Dhu who was killed in Western Australia. It’s utterly harrowing viewing.

Internationally, there’s almost too many situations to even consider, but I can speak to the images surrounding the Syrian refugee crisis. That tiny, beautiful body of Alan Kurdi lying lifeless on that shore, the procession of images coming out of Aleppo in recent months and all that surrounds that situation, is what has contoured this record, either directly or indirectly.

I wanted to try and find a way to navigate this perpetuity of distress and states of trauma, and find a way that I could comprehend and process how these situations make me, as I assume others, feel. The record is the navigation device and the response in one.

What was your approach to communicating these philosophical concepts through sound?

The wonderful things about art, music and sound more generally is that they're relational and invitational.

For me, when I was creating the work, these concepts were centrally placed in the ways that I approached the music and the composition. Some of these connections were very direct; the use of particular field recordings and found sounds for example directly relate to some of these conflicts and machinery used in the situations I’ve spoken about.

Other connections are less readily available in the work; they are inferred rather than explicit and I feel that’s important as the record will mean different things to different people.

I think there’s nothing worse than being didactic with art making, so for me I am less interested in the music telling the story as inviting people to find their own narrative in it. Ultimately we can only ever know our own senses, shaped through our own socio-cultural and political backgrounds. That goes for music and anything else really.

A very simple example I can give of this, from Brisbane where I live, is the use of military aircraft during Riverfire, an event that sits within Brisbane Festival. I find myself thinking how privileged I am, like many people in this city, to be able to witness those machines as pure spectacle. It’s a kind of pornography of war, arousal through disassociate spectacle.

For someone else though, who has been in a situation of conflict, those planes represent nothing but their actual use, which is to destroy and to kill. They exist for no other reason than this and yet most people at this event simply have no cause to make that connection.

For me, 'Cruel Optimism' – and music more generally – is an opportunity to open conversations and explore ideas. I know from my youth, I learned so much through reading interviews with various engaged cultural figures. I see every conversation, like this for example, as a way of contextualising the work and hopefully offering some food for thought.

Do you feel the album and its subject matter retains relevance within the current discourse of the global, political climate?

I’d hope so. It is informed by and concerned with the flow of the current political crisis. I also feel that Berlant’s 'Cruel Optimism' is a wonderful tool for the analysis of current expressions around Brexit and Trump that we have to reconcile. I feel strongly her work is a critical tool through which we can recognise how it is we arrived here.

Beyond her work as a foundation for the record, I believe strongly that art, of which music is one of the pillars, has a huge contribution to make towards activating and cultivating particular social and cultural phenomena. Music is one of the zones at which we can find new meaning and understanding with our senses.

Music is an invitation from one person or group of people to another to share time together. It’s a temporal exchange. I think this is specifically important when you start to consider the concert setting as a place of public assembly. In these settings sound engulfs all with equal tenderness.

What sets this album apart from your previous releases?

'Cruel Optimism' is without question the most difficult record I have ever made. In my mind’s ear, I have a very specific condition I wanted to create. To co-opt Lemmy’s line, I wanted ‘everything denser than everything else’. I wanted to reach a point of saturation that transcended anything I had done to this point. That took a great deal of experimentation and time to realise.

What was wonderful about that investment though is that something new arrived for me. The search was not in vain. I found many new ways of aesthetically and technically approaching the raw materials that form this work. I came to recognise that amplitude and density are not tied together, but are relational, something that I will no doubt seek to explore further.

How different is the album we hear, compared to how it sounded in your head when you were conceiving it?

It’s not exactly what I heard in my mind’s ear, but when I listened to it as a final master I felt satisfied that it had achieved what I set out to do. You always have to be left wanting more, to be hungry. The moment you’re not, it’s either time to move on or it’s time to die.

You worked with a number of contributors for the album, such as Mats Gustafsson, Chris Abrahams and Vanessa Tomlinson to name a few. What did each of them bring to the writing and recording process?

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the players on this record. I wanted to return to a more collective approach to music making, even if the collaborations were one to one for the most part.

I wanted to be surprised and there’s nothing quite as beautiful and surprising as another human mind. No one approaches things in the same way; they might be similar, but in the detail there is often very telling and important learnings. All the players were very generous to me, they put up with my esoteric notes and provocations and through their performances this record was most certainly transformed again and again.

To have to respond to those iterative shifts was challenging, but very much more rewarding that I could have hoped.

Will you be performing the album live any time soon?

I will. This record is very much created with the idea of translating it a physical experience for audiences.

Aside from your music, are you working on any visual art installations at the moment?

Yes, that will likely become the focus of a good chunk of this year. Right now I am developing a multi channel iterative sound work explore of voice, as a political tool. It’s exploring the idea of ‘people’s voices’ rather than ‘the people’s voice’, which is by design exclusionary.

I’m interested to bring together voice in a way that is about unity in difference or perhaps moreso unity in diversity. I think this is a critical recognition at present. There’s so much retrograde territorialisation; socially, politically, geographically, we need to work against this step back into the 20th century.

There’s a set of sound sculptural pieces exploring protest more directly too that I am developing. I’ll also be working on a piece that explores questions of phenomenology and audition, how it is we understand ourselves through audition and what the denial of that sense means for our capacities to understand the world. I enjoy greatly these larger scale projects, they offer a set of challenges that are entirely different to the other projects I work on.

Looking ahead, what's your plan for 2017?

Right now I am finishing a PhD. It is concerned with listening… I am hoping to finish it VERY soon, as the road is no place for such pursuits.

'Cruel Optimism' is available now.