It's July 20, 1969, and actor Keir Dullea is about to play a small role in history.

The Apollo 11 Eagle Lunar Module has landed on the moon, and the world is waiting for Neil Armstrong to emerge and take his first small step onto the surface. The problem is that he's not in any particular hurry to do so – six full hours pass before Armstrong opens the hatch and begins his descent, leaving the world's television networks with an awful lot of time to kill.

CBS decides to recruit talking heads to help fill their broadcast, including legendary author and futurist Arthur C Clarke – a lifelong proponent of space travel and former chairman of the British Interplanetary Society, widely regarded as the “prophet of the space age” – and Dullea, who had, ah, starred in a movie about space one time. (The film was '2001: A Space Odyssey', co-written by Clarke.)

“I was doing a film in the Bahamas,” Dullea remembers. “My agent called and said, 'They want to fill time, because it's going to take a lot of time to wait until the astronauts step out'. They didn't come out for hours, even after the landing! So they flew me up from the Bahamas on my day off from the film, and I was interviewed along with Buster Crabbe, who played Flash Gordon in the early B-grade movies.

“Suddenly the interview was over, and somebody came running into the room saying, 'Come into the control room! They're coming out, they're coming out!' So I went into the control room and I sat down to watch the astronauts emerge.

“I looked to my left, and there was Arthur C Clarke. He had tears in his eyes.”

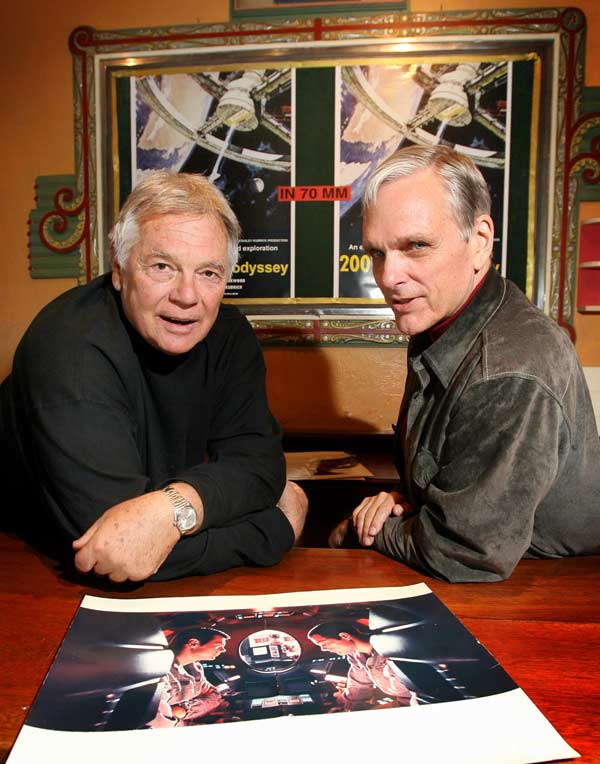

Armstrong's moon walk earned rave reviews, but the reaction to '2001: A Space Odyssey' had been decidedly mixed. Now regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films of all time, we're used to thinking of the Stanley Kubrick film as an untouchable masterpiece, but that was far from the concensus opinion in 1968.

“It got very mixed reviews,” recalls Dullea, who played the lead role of astronaut David Bowman. “50 percent of them were terrible reviews. I don't just mean 'bad' – I mean terrible. The other 50 percent were okay, and some were quite brilliant reviews, but you wouldn't guess from all those bad reviews that it would end up being the iconic film that it has become.”

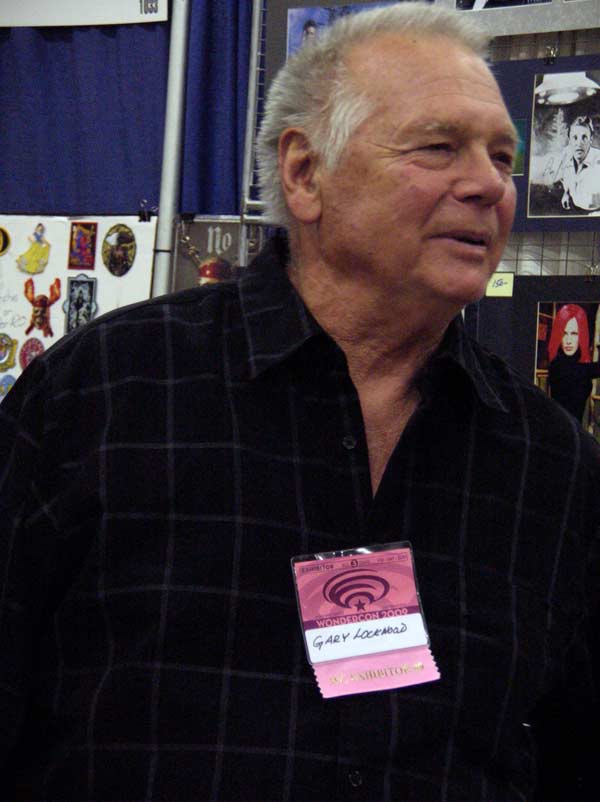

Gary Lockwood, who co-starred with Dullea as astronaut Frank Poole, has a similar memory. “A lot of people didn't like it. Critics turned away from it big time... I had said some very bold things [about the film], and was taken to great task for it by the press. Some of them actually apologised to me later. Not many! There are too many egos in show business, but one or two admitted they were wrong.

“The local papers in Los Angeles loved the movie, actually. We premiered in Washington, then New York, then Los Angeles, and the east coast of America and the west coast are much different. The west coast is much more high tech, you know?

“When Arthur C Clarke, [editor] Ray Lovejoy and I were on the airplane for LA on the morning of April 5, Arthur asked me, 'What do you think about tonight? Do you think we'll have another rough night?' And I said, 'Not tonight, baby. We're going to a movie town.'”

Despite the mixed reviews, neither Dullea nor Lockwood felt crestfallen about their roles in the film. “I knew that we were in a great film,” Dullea says. “From my own point of view, I knew that I had worked with this great genius. When you work with Stanley Kubrick, you're aware that you're in the presence of genius. He was an extraordinary director. I loved every minute of working with him. He was very supportive, very quiet, never raised his voice. He was the most prepared director I've ever worked with. And I knew from the reactions of people – forget about the critics, I just knew from the reactions of audiences that a great number of people really thought this was a hot film.”

Lockwood also has fond memories of working with Kubrick, despite the director's reputation for being a hard taskmaster. “Well, every actor has a different history with him, and I can't speak for others. In my case, I got along extremely well with him, and I didn't have to do very many takes like some people did. I don't know. I'm a bit more of a technical kind of actor. I'm a painter and an architect. I make specific points when I work, so I think that saved me from having to do a lot of takes.”

Today, Lockwood insists he “surely knew it would be one of the better movies ever made”. Dullea recalls thinking it would be “a very important film for that year,” but admits he had no idea he'd still be talking about it 46 years later. “Would the actors in 'Citizen Kane',” he asks me, “have known that they'd be studied in film schools 75 years later? You never know a thing like that.”

Dullea and Lockwood are both well aware that '2001' is what they will be remembered for. It routinely finishes on top of lists of the greatest and most influential films of all time (even the Vatican rates it as one of the 'Top Ten Art Movies' of all time), and the likes of Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Tom Hanks have credited it with inspiring their careers. It's the film that continues to get Dullea and Lockwood invited to conventions around the world (both men will attend Supanova this month), and the clear highlight of both of their long, distinguished careers on stage and screen.

Dullea, 77, made a career out of playing emotionally disturbed young men in acclaimed films like 'David And Lisa', 'The Thin Red Line' and 'Bunny Lake Is Missing' before he was cast in '2001'. As Dr David Bowman, his generically handsome features served as the canvas for Stanley Kubrick's psychedelic fireworks in the final act of the film, and he got to utter one of cinema's most famous lines (“Open the pod bay doors, HAL”).

Despite the legacy of '2001', Dullea never became a household name. He reprised the Bowman role in '2010: The Year We Make Contact', a lesser sequel to '2001' that was made without Kubrick's involvement, and he starred in the cult 1974 horror flick, 'Black Christmas', but the New York actor's most interesting (and consistent) work has come on stage, including a definitive turn as Brick in a Broadway production of 'Cat On A Hot Tin Roof'.

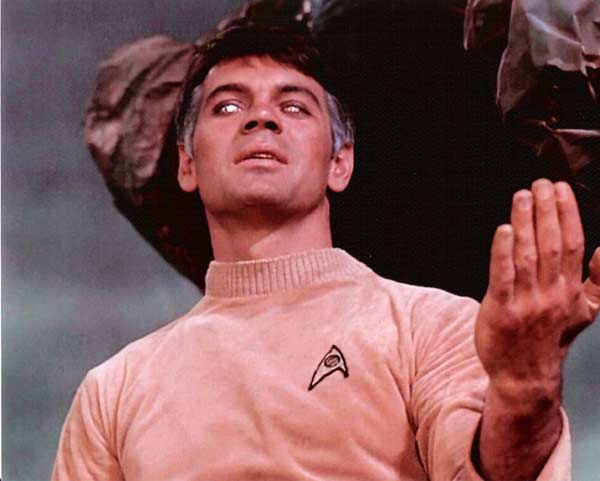

'2001' was actually Lockwood's third brush with immortality. The Californian co-starred in two Elvis Presley movies in the early '60s, before playing the lead role in 'The Lieutenant', Gene Roddenberry's first television series. When Roddenberry created 'Star Trek' a couple of years later, he cast Lockwood in the pilot episode as sympathetic villain Gary Mitchell.

“[Roddenberry] was a very interesting guy, a bit of a scallywag like I am,” Lockwood, also 77, remembers. “You know, he was a lot brighter than most of the people I've worked for... He and I discussed ['Star Trek'] at great length a few times [on the set of 'The Lieutenant']. As a matter of fact, he made a pilot and it didn't sell. At that time, I was kind of famous, so they told Roddenberry to make a second pilot with me in it. So that became 'Where No Man Has Gone Before', and that's the pilot that got 'Star Trek' on television.”

(Lockwood wasn't as confident in 'Star Trek' as he was in '2001'. “That was a bit of a joke for me,” he admits, “because I played a godlike character, which I thought was a little bit absurd.”)

As further proof of its immortality, '2001' returned to prominence last year when 'Gravity', Alfonso Cuaron's similarly realistic space movie, was often cited as this generation's answer to Kubrick's masterpiece.

“You know, I think 'Gravity' is pretty spectacular,” Dullea says. “I was very impressed. The only thing is... you have to ask, what is it that makes '2001' kind of unique and special? Part of it has to do with the fact that Stanley Kubrick never tied up a plot in a very convenient knot. There's always ambivalence.

“I remember, at the time, hearing raves from Catholic nuns about the film, and raves from atheists and agnostics about the film. Now, they obviously had different experiences, but that's part of what's so exciting about '2001' – it will hold all of those interpretations. I don't mean to be overly simplistic about this, but you could say that the film is like a giant Rorschach test.

“So in that respect... [Lars Von Trier's] 'Melancholia', which isn't a space movie, but is without doubt a science fiction movie, maybe comes closest to my feeling of what makes '2001' special. 'Gravity' is exciting, and the computer generated effects and the performances are marvelous, and I really enjoyed it. But still, if you're trying to say, 'What is it that makes '2001' so special?', I think it's what I just said. It's the mysterious ambivalence of it.

“Kubrick never explained things. Most people feel that you have to explain things for an audience. I'll give you an example, a perfect example of that. When the lead ape throws the bone up into the air in triumph at the beginning of the film, and it morphs into a space vehicle... I've only recently discovered, or learned, that wasn't just a space vehicle. That was a nuclear weapon in constant orbit around the earth.

{youtube}qtbOmpTnyOc{/youtube}

“But Kubrick didn't make that obvious on screen. You had to know about it, you had to have read the book. It's kind of laid out a little bit in the book that [Kubrick and Arthur C Clarke] wrote together. Arthur C Clarke presents the situation that the United States and the Soviet Union are in total stand-off, and that each of those countries have nuclear weapons in constant orbit around the earth, any one of which can be sent to earth at the push of a button.

“So what he had was the first weapon discovered by primitive man morphing into the most recent weapon. But he didn't tell the audience that! The film is filled with stuff like that. He never felt it necessary to over-explain.”

Lockwood is similarly diplomatic towards 'Gravity' – “That was a nice movie, it was made very nicely” – but he's unimpressed by most of the science fiction films that have followed '2001'. “They're mostly just Cowboys and Indians,” he says dismissively.

He's more interested in how real world science has followed the lead of '2001'. “I enjoy the fact that there's a space station, and that different countries collaborate. I think that's nice, I think that's good for mankind. Mankind sure as hell can't get it together in any other area. At least they're not shooting each other up there. That's kind of cool.”

Despite his character's distrust of HAL 9000, the artificial intelligence that controls the systems of the Discovery One spacecraft in '2001', Lockwood has come to embrace Siri. “I've said some slightly uncouth things to Siri,” he laughs, “and she's said, 'Sorry, Gary, but I don't think that's an appropriate question'. I think that's great.

“I do have an iPhone and I love having it. It's a fantastic tool. Some people are very proud that they don't have television, they're very proud they don't have an iPhone or any other kind of smartphone, they're very proud they don't use computers. But all these tools and things that we invent, they're basically toothpicks. If you have something in your tooth, you get a toothpick. But if the toothpick is high tech, it seems to be intimidating to some people.”

Dullea, on the other hand, happily admits to being intimidated. “I use an iPad a lot, but I'm a caveman when it comes to computers,” he laughs, well aware of the irony. “My wife is much better than I am, but she would tell you she's not very good either. I do email, and I Google things, and that's about it. There's not a lot that I can do with a computer.”

I ask Dullea if he's ever asked Siri to open the pod bay doors. He says he hasn't, but he's keen to try it out. I say goodbye, more than a little happy to know one of the most memorable lines in sci-fi history is about to be uttered one more time.