In 1974, a young Robyn Archer appeared in the Australian premiere of the Weimar era Brecht/Weill satire, 'The Seven Deadly Sins', a production written by the famed German duo while living in exile, having fled the incoming Nazi regime that ruled over their homeland.

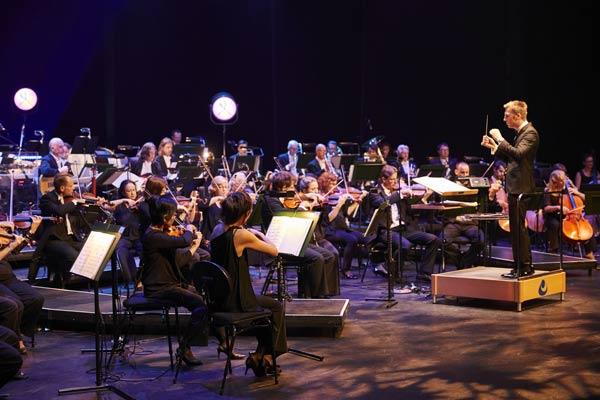

In Gigs At Granger 2, 'The Fortunes Of Exile', Robyn, along with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (ASO), long time accompanist Michael Morley and accordion and banjo player George Butrumlis, will explore the songs, music and lives of German composers who, like Weill, escaped totalitarianism and forged new lives, with varying success.

Robyn talks about the show.

You began singing the work of Weimar era German composers in the 1970s and are internationally recognised as one of the finest performers of this repertoire. Can you tell us a little more about why this era has had such an enduring appeal for you as an artist?

The Weimar era was an amazingly fertile artistic period which came in the wake of the horrors of the Great War of 1914-18. Most artists had direct experience of the war, some on the front, some behind the lines, but all saw the horror of the aftermath – from the visual art of George Grosz to the architectural response of Margarete Schutte-Lihotzky who understood that so many Austrian widows would need new domestic design. Then came the years of hope and relief, the happier songs, the flourishing of Bauhaus design. But all the time they were ‘dancing on the volcano’. And with the rise of Nazism, little more than ten years later, many mainstream artists were not quiet about their political views. It was a dynamic time which brought out many brave, but still accomplished, artistic statements. I admire that.

Can you tell us a little about the composers that you will be featuring in this show, and their fortunes under the Nazi regime?

All of the composer/lyricists whose work we are singing in 'The Fortunes Of Exile' were at the peak of their careers during the Weimar period. While there were many artists who did not overtly disagree with what the National Socialists first proposed and then enacted, the writers/composers we feature here were all outspoken critics of the regime. For that reason they all had to leave Germany. Had they not fled they surely would have been arrested and probably murdered. Imagine these creatives, in their 30s, having huge successes and then having to up sticks with their families and simply start again from scratch in countries, usually America or the UK but temporarily also Denmark, France and Holland (all also became unsafe with Nazi invasion), where as Germans or Austrians they were probably treated as aliens and under suspicion. In order to survive, most of these highly intelligent and creative artists now had to write the schmaltz that the popular taste of their adopted countries demanded. That’s what this concert is about.

With our world becoming increasingly akin to the years preceding the Second World War, what lessons do you think we can learn from the past?

The question is really why have we not learned the lessons of the past. In the past couple of years we have seen situations in America and Britain almost identical to the pre-conditions of the rise of Nazism in the late 1920s and then the '30s. With the collapse of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929, ripples ran through the world and Germany suffered a deep depression. Bertolt Brecht wrote with brutal precision about the poverty and despair this created. It took just one powerful orator to tell these unhappy people that he had the answers, he could make Germany great again, and had a final solution to their plight. In America and Britain a great swathe of people felt disenfranchised and longed for a time past when they were more comfortable. The results of both the Brexit referendum and the US election depended on a culture and rhetoric of blame – mainly race-based. How very sad that enough people again fell for the misleading rhetoric of simple and dangerous so-called solutions. Even more telling, I question whether we are now accepting into our country the political exiles of our times with the kind of generosity which the USA the UK and Australia displayed at that time. How many political exiles who were at the peaks of their artistic, and other, careers, have had to upsticks with their families and start again in a country where they are viewed with suspicion? How many poets, painters, composers are now driving cabs, or packing chickens on the midnight shift in vile warehouses? Why can’t we learn?

You have collaborated with Michael Morley for over four decades. What do you value in him most as an accompanist?

Michael has been for decades, and continues to be, an invaluable collaborator. Of course he is an accompanist of enormous precision but with the ability to ‘follow’ as well as to lead. He knows precisely how a work should be sung, and will always advise what’s written, but then allows me to vary tempo, dynamics, even actual notes, according to what I feel the performance demands. He is completely accurate but wholly flexible, and that’s a rare combination. But Michael is also a learned Professor of Drama, so he is sensitive to the business of performance and is wholly supportive of me on stage. His knowledge of theatre, music and poetry, especially the German work of this period is second to none, and so as I put different programmes together, he is the most reliable source of background detail, new ideas and resources. He is also an expert in German and French language and translates a lot of our repertoire. In short, I couldn’t have done what I have done over the last 30 years without his expertise. Finally, he is a splendid cook and rehearsals at his home are always generously catered for.

Can you tell us some of your favourite memories of appearing with the ASO in your career?

The most important appearance with the ASO was my very first leap into the arts in 1974. Until then I had been an entertainer in any number of genres and at the time was singing rude ditties in the cellars of the Old Lion Hotel. I had also been singing the repertoire of the American civil rights movement for about ten years – the protest and ‘folk’ songs of our time. The invitation from Justin Macdonnell, then the administrator of New Opera SA, to sing 'Annie 1' in the Australian premiere of Brecht/Weill’s 'The Seven Deadly Sins' led to a complete change of direction in my career. Never having learned music, I was coached painstakingly by repetiteur Chester Schultz, and I had never sung with an orchestra. The production opened the Space Theatre at the Adelaide Festival Centre. I was terrified, but under Wal Cherry’s direction I pulled it off. It led to The Threepenny Opera the following year, John Willett was dramaturg, and he then invited me to London to the Royal National Theatre and remained my mentor for the rest of his life. Another two men – Justin and John – without whom I could never have done what I have. I subsequently did another programme of Brecht/Weill /Eisler songs with the orchestra under David Porcelijn in the mid '80s and had great experiences, as Artistic Director, in programming the orchestra for my 1998 and 2000 Adelaide Festivals, but that initial leap in the '70s remains vivid.