Friday night's (13 September) world premiere performance of ‘Oscar’ by The Australian Ballet with Orchestra Victoria is held at that grand old dame, the Regent Theatre in Melbourne, all done up in red carpet for the beautiful people who step out in style in their gowns, tuxedos and flamboyantly dandy attire. But the real star on the night is the tempestuous and tantalising ghost of Oscar Wilde.

Artistic Director of The Australian Ballet David Hallberg welcomes all, saying, “. . .We are making history. Not only are we presenting a brand-new work, but a story not typically seen in classical ballet. Representation for all people is paramount to our vision of the future.”

Truly, it is easy to wonder where the ballet would be without all its well-known queer patrons, creators and dancers, but the ballet world usually portrays the stories of straight lovers. A ballerina is the female dancer who is typically the centrepiece of the story. In fact, there is no English word that distinguishes a male dancer from a female dancer, because males aren’t typically the focus of the action. Here, they are elevated from beautiful agile lifters of the principal ballerina to the main attraction, stars in their own right.

In turning this tradition on its head, ‘Oscar’ uses two of Wilde’s most famous pieces, 'The Nightingale And The Rose' and 'The Picture Of Dorian Gray' to full effect, illustrating the many lives of Oscar Wilde. In this telling, the first piece of the narrative is a poem and illustrates the futility of unrequited love through the death of the Nightingale, while ‘The Picture Of Dorian Gray’ is used in act two. It is the story of a man besotted by his own dashing image of perfection. The subject of the portrait betrays and defiles this perfect image with crass misdeeds in his real life, which are in turn reflected in the portrait, which becomes more repulsive with each wicked act.

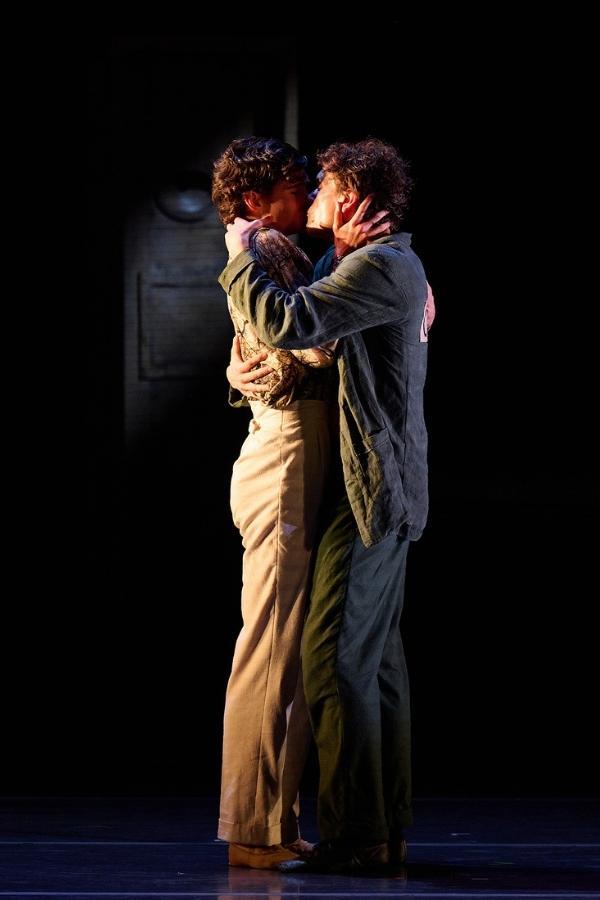

‘Oscar’ embraces Wilde the writer, his fame and his queer life and loves. It revels in the sexuality and sensuality of “the love that dare not speak its name”, a phrase that was mentioned during Mr Wilde’s 1895 trial for expressing his love for men. The dazzling and energetic prologue is set in the courtroom of that trial, as the once mighty darling of high society is incarcerated for two years' hard labour after a ferociously public trial for Gross Indecency.

Image © Christopher Rodgers-Wilson

And this is where we meet in act one, in a flashback memory in his prison cell. Oscar reads 'The Nightingale And The Rose' to his wife and children in a scene that conjures up an idyllic family life and sets the pace for this act.

Oscar’s love interests are defined throughout this production with careful attention paid to balance the contradictions of his love for his devoted wife Constance (Sharni Spencer) and two sons, delicately juxtaposed and contrasted with his love and desire for his first love interests, including his first relationship and most enduring friendship with Robbie Ross.

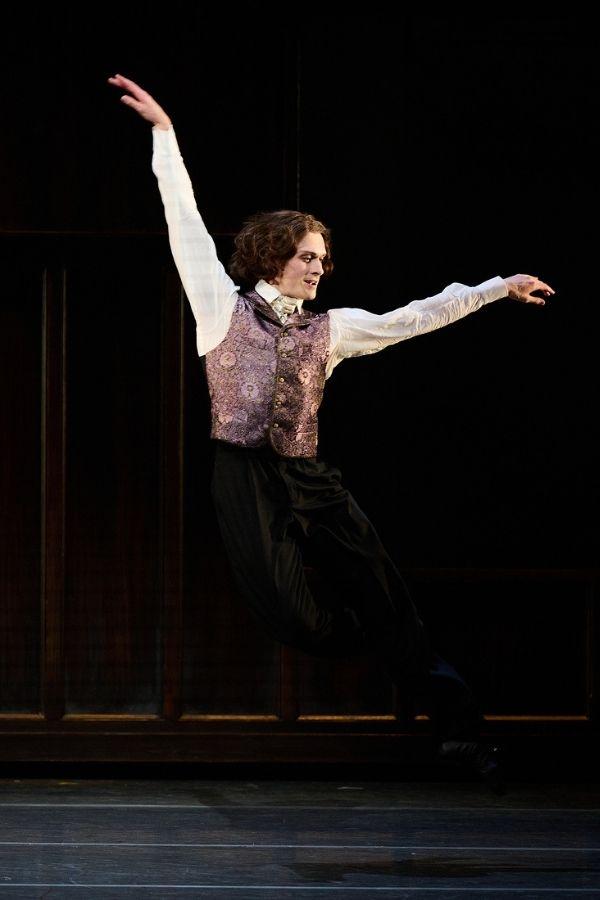

Oscar, as played superbly by Callum Linnane, is a mesmerising kaleidoscope of movement, grace and athleticism – as fluid as water. Linnane excels in presenting the many faces of his character in a demanding role where his emotional range shifts between longing, loving, trusting, naive and sometimes sordid – all enacted with precision choreography by Christopher Wheeldon.

The character of Robbie Ross is played by Joseph Caley, who deftly manages the tightrope balancing act between Ross’ initial flirtation and physical longing for Oscar, to his great friendship and protection of him in his later life. This perfectly contrasts Oscar’s relationship with the beautiful young Bosie, played by Benjamin Garrett, who manages to encapsulate the recklessness and the aching honesty and deceptions that marked their eventually disastrous love affair, expressed through thrilling and flawless movement.

Ako Konda is perfect in the role of The Nightingale, which she fully inhabits with poise and grace, her body mimicking bird-like movements as she flies and pirouettes in her glorious costume. The lavish designs by Costume Designer Jean-Marc Puissant are lush and indispensable to this production.

Image © Christopher Rodgers-Wilson

As Oscar becomes bolder in seeking the love he desires, we time travel with him to an evocative, colourful and secret underground world of orgy and the scenes that he frequents, ultimately to his demise. It is a thrilling and seductive journey – a literal, visual and aural feast for the senses marked by stand-out performances by Marcus Morelli and Cameron Holmes as hilarious, joyful drag queens at the bar. The stunning orgy scenes are hypnotic and bold, a viscerally human interpretation of intertwined bodies and realised longings.

Act two tells the second half of the ballet with what is arguably Wilde’s best known work 'The Picture Of Dorian Gray’, as he descends into madness, loneliness and pain due to the rigours of hard labour and the tinnitus he suffered during his incarceration. Both conditions are expertly conveyed by an assured and grandly immersive soundscape, created by Joby Talbot and performed live and note-perfect by Orchestra Victoria.

In a heart-stopping final act, Oscar's sad emotional and physical descent are punctuated and frenzied to perfect peak-pitch level, both musically and by dance via visits to Wilde’s tortured conscience. In his deep devastation, financial ruin and surrender to the squalor of prison. At last, 'The Picture Of Dorian Gray' sees this tragedy to its bitter end, with the portrait restored to its initial beauty as Oscar himself disintegrates.

Christopher Wheeldon’s modern masterpiece is an empathetic, moving telling of Wilde’s genius as a writer and of the ruinous scandal that engulfed his private life. Wheeldon's deep admiration, affection and care of the memory of Oscar Wilde shines through in every moment of this production like a lover's letter.