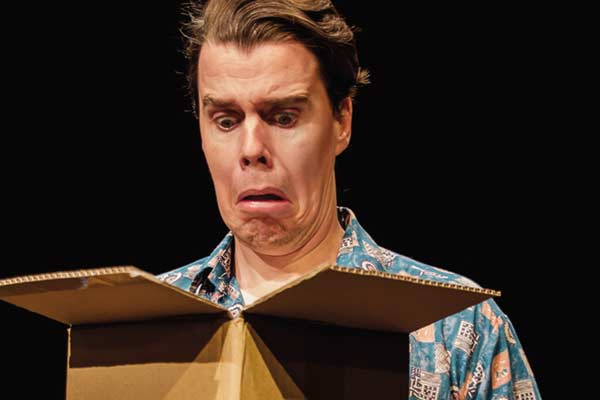

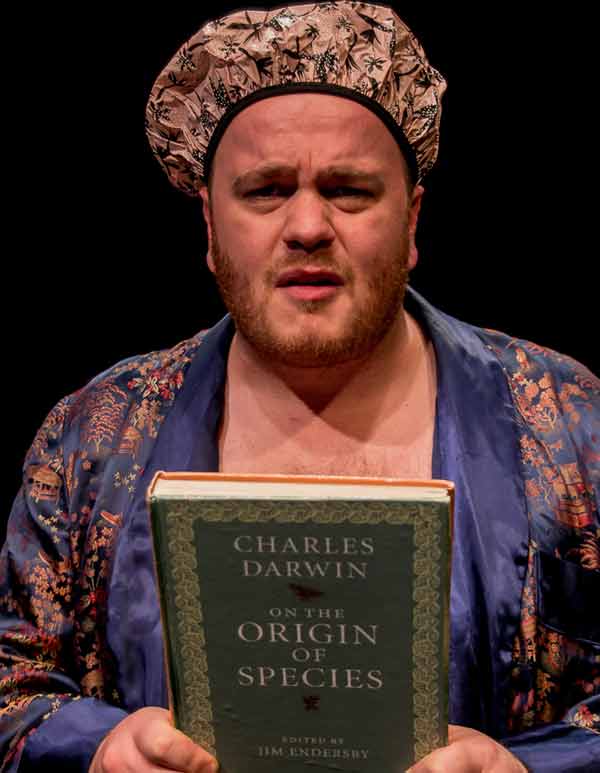

With Marius von Mayenburg’s 'Perplex' to be staged at The Bakehouse Theatre this August, Director Joh Hartog continues to indulge in his fascination with German theatre.

We speak to Joh about the baffling absurdity of a play that has been described as being “the perfect play for the Age of Trump”.

'Perplex' has relevance to the works of Nietzsche and Beckett, both of whom attempted to resolve the meaning of existence. What answers does the play give to this search for meaning?

The attempt to resolve the meaning of existence is, of course, as old as humanity. After WW2 with its unimaginable destruction of both people and material, various playwrights have needed to move beyond constructing what you might call a benign and caring universe which has no purpose or meaning we could rely on.

Absurdists (such as Beckett and Ionesco) expressed that concept particularly in terms of the unreliability of everything around us. Anything can happen and nothing is any less certain than any other thing.

The sun is likely to come up in the east, but if it came up in the west tomorrow, no one in an absurd play would bat an eyelid. One of the conclusions you might draw from this (as the existentialists do) is that we should not look to the universe or God to provide us with meaning for our existence, but that we have to determine meaning for ourselves. That includes our approach to morality and our general sense of what is ‘right’ and what is ‘wrong’, which is where Nietzsche comes in.

The question remains then to what extent we can share moral precepts and notions of right and wrong by agreement rather than by divine order. This is the subject of a fair bit of writing by Camus and Sartre, for instance.

While 'Perplex' examines profound philosophical questions, it is also full of laughs. Where does the humour come from in this work?

Humour is the only antidote to what is a deeply disturbing reality. The notion of an uncaring, indifferent universe does not sit well with us, and can give rise to both the euphoria of absolute freedom and the depression of total meaninglessness.

The best way to deal with that is by laughter at the ‘absurdity’ of it all. If you chart the development of Ionesco, for instance, he started off with his very funny 'Bald Primadonna' in the '50s and ended his writing career (long before he died) with 'Journeys Among the Dead', which is hardly a barrel of laughs. I think he stopped writing 12 years or so before he died, because going further down the path he was on can only lead to self-destruction. So humour is our only solace. And it beats crying.

This is a work that questions the nature of reality. Our apparent global reality is quite bleak right now. Does this work offer an escape?

That’s two versions of reality really. The nature of reality is a philosophical question and relates very much on our often subjective perceptions. Some would say there is no objective reality, because everything we see and do is filtered by brain activity.

Global reality is also very flexible and our perception of it more controlled by the media than by philosophy. The perception of bleakness is largely caused by the 24 hour news cycle which foregrounds the negative and the disastrous. And if events are not horrible enough by themselves the media never minds blowing it all out of proportion a bit more.

Doing that decade after decade, it must have an effect on how we perceive the world to be. Maybe our global reality is not bleak at all, but we have been to believe it is.

'Perplex' had its English language premiere with the Sydney Theatre Company in 2014. When were you first exposed to the work?

I have been very interested in German plays for a long time. I think they are at the cutting edge of contemporary theatre. Unlike the English speaking world they play more with structure and different forms of experiencing.

In the recent past I directed 'Arabian Night' and 'The Golden Dragon' by Roland Schimmelpfennig, 'Innocence' by Dea Loher and 'Biography, A Game' by Max Frisch. All of these are theatrical constructions that takes a fresh look at our relationship to stuff happening on stage, moving away from straight naturalism: a linear story told behind the fourth wall as its one and only (imagined) reality. I love playing with different and contrasting realities that keep the audience guessing.

Marius von Mayenburg is an important playwright that many Western audiences may not be familiar with. What appeals to you about his work?

German playwrights are far more adventurous that what we are used to here in Australia. They often take enormous risks and I am sure they do their fair share of flops between some outstanding successes. I first came across this play in a book before I became aware it had been premiered in Sydney in 2014.

I loved it immediately, both for what it said and its off-the-wall humour. By the way, there is actually an established link between Australia and Germany. Several of our better directors have worked both here and Germany, such as Benedict Andrews and Barrie Kosky.

'Perplex' plays Bakehouse Theatre from 15-25 August.