Dramatic readings have gone out of fashion over the years. We like our theatre events to have pizazz: fog machines, lighting changes and people flung about the stage like outfit choices before a date.

Three people sitting on chairs, reading aloud? For it to feel like more than a financially lucrative classroom, the readers have to be confident in their ability to make their audiences care. For that to happen, they need high-quality writing.

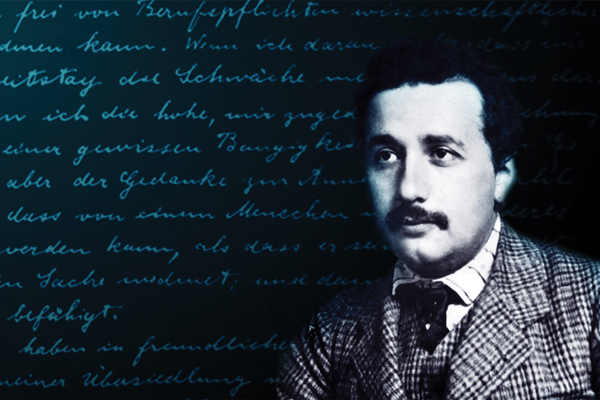

It’s hard to imagine a dramatic reading showing hallmarks of a celebrity gossip fest and yet ‘Dear Albert’ manages it, taking the enigmatic genius of Albert Einstein and looking beyond the wild hair and intellectual prowess at the vulnerable human beneath.

The truth is, most of us know only the bare basics: smart, science nut, wacky hair and sage-like eyes, but still we claim to know who Albert Einstein really was. We tend, sadly, to assume perfection in those deemed celebrities, regardless of their actual failings. And when those failings inevitably come to light, and the celebrity is revealed as ultimately human, society is quick to condemn.

In ‘Dear Albert’, performed as part of the World Science Festival Brisbane, Einstein’s womanising and inability to commit to relationships the way he committed to his work isn’t thrown about to make a villain of the man. Instead, we get to see the cost of fame and success on a man who’d thought himself on the path to a quiet, scientific life.

‘Dear Albert’s’ writer, Alan Alda, knows a thing or two about the erasing power of celebrity. Though he is a founder of the World Science Festival, and a vocal proponent for the sciences, he’ll always be known first as Doctor Hawkeye Pierce from ‘M*A*S*H’. It’s Alda’s innate understanding of the dark side of celebrity that gives him the ability to so compassionately explore Einstein’s humanity.

‘Dear Albert’ isn’t about shaming, nor about dismantling the larger than life idea of Einstein we seem to hold. Instead, it’s revealing the real man, and his physical impacts upon the world.

Alda’s belief is that when we see only a fraction of the person, or the idea, we lose out. To hold Einstein up as perfect leads future generations to believe that scientists (or celebrities) must be perfect, and must have nothing in their lives beyond the work.

However, when we look at the whole man we get a sense not of failings but success. We can see that Einstein was more than scrawled equations, but a man with the same concerns and problems we face.

And, more importantly, we have a chance to see that such problems can be overcome and that greatness is possible even when you don’t have every opportunity thrown at you from day one.

A pretty good life lesson from three people reading in chairs.