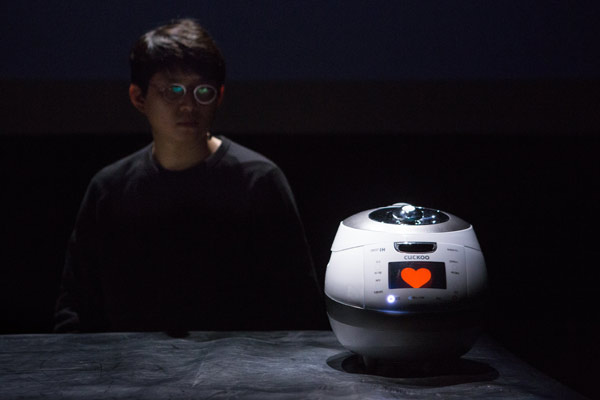

In 'Cuckoo', Jaha Koo’s second work in a trilogy on the origins of sadness, the Belgium-based Korean multimedia artist is joined on stage by a trio of singing robotic rice cookers to trace the roots of the affliction that is plaguing hearts and souls in Seoul.

As a child of the 1980s, Jaha Koo was in his teens when the Asian Financial Crisis devastated his homeland of South Korea; it was an event which opened the door for the intervention of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) into a nation which, until then, had remained insular and sheltered from the neo-liberalism that had swept across the west in the 1980s, led by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

According to Jaha, the IMF and western ideology were unwelcome guests.

“In 1997, I think that was the turning point: neo-liberalism by the United States arrived. After that the economic structure totally changed and the country was burdened with debt.”

“The younger generation had to take a burden even though they didn’t expect or didn’t want it. The economic [changes] not only appeared, it’s also related to the political department and also the social labour policy is getting poorer and this pressure made lots of effects: Family problems and personal issues. We found that the suicide rate is getting higher, much more than Japan, for example. This problem has only been for the last 20 years, but nobody really thinks about how this happened after 1997.”

Neo-liberalism, with its emphasis on the rights of the individual over the wellbeing of society, Jaha explains, is at odds with traditional Korean values.

“South Korea, for example, traditionally is based upon Chinese Confucianism which developed into Korean Confucianism. Family is much more important than the individual and the country is much more important than the family, but people can see so much corruption from the government and then the only thing that people can trust is family.”

Image © Radovan Dranga

If you cannot trust the government and there is no society, only the self-interested individual economic actor, Jaha asks, then what happens to those who cannot look to family for help?

“In 'Cuckoo', I wanted to talk about the people who can’t be taken care of by the family, for example, so there is now an empty space for the individual.”

The three Cuckoo brand rice cookers that join Jaha on stage, then, are multifaceted metaphors. Rice, as a staple of the Asian diet, represents the health of society; the pressure cooking device represents a 'society under pressure'; as technological devices replace tasks that formerly required human intervention, they represent how our humanity is being replaced by machinery; and finally, as a 'must-have' consumer item, the Cuckoo rice cooker is emblematic of consumerist brainwashing.

While the Cuckoo rice cooker phenomenon is peculiar to South Korea, the themes explored in the work have resonated internationally, Jaha says.

“The important thing is when I make my work, it’s not only for a Korean audience, even though I’m talking about Korean stories and Korean social problems, but this show is not only for Koreans. It can be transformed to each local language and to each local problem and they can understand.

When Jaha performed in Athens in the wake of the Greek Financial Crisis, he received an extraordinary response.

“Many of the audience [members] came into my dressing room even though they were not permitted in my space. I felt that they had a crucial urgency to discuss much more about what’s going on in Athens and what’s going on in Seoul.”