HIV-positive Indigenous Australian dancer and choreographer Jacob Boehme’s first encounter with a person diagnosed with the highly stigmatised human immunodeficiency virus was in the 1990s.

It was a time when artistic works such as the Broadway classic musical 'Rent' and the Academy Award-winning motion picture 'Philadelphia' were raising awareness about the plight of HIV and AIDS sufferers, building empathy and reducing the stigma in the process.

In the past three decades, advances in medical science have meant that an HIV diagnosis needn’t be a death sentence, yet for Indigenous Australians, it too often is, as Jacob explains.

“I remember being on a board of an HIV organisation years ago when these new stats around spike groups [emerged]. This was when they were saying that the end of HIV in Australia was nigh but yet in the same research, HIV detection in gay Aboriginal men had gone up 100 per cent.”

“That previous year there were about 80 AIDS-related deaths. In a country where we have mostly free and up-to-date medical treatment, there should not be AIDS-related deaths in our country, so the hypothesis was that a good proportion of those deaths were people who were either willingly or deliberately not seeking treatment and most likely they were out and living in remote Aboriginal communities.”

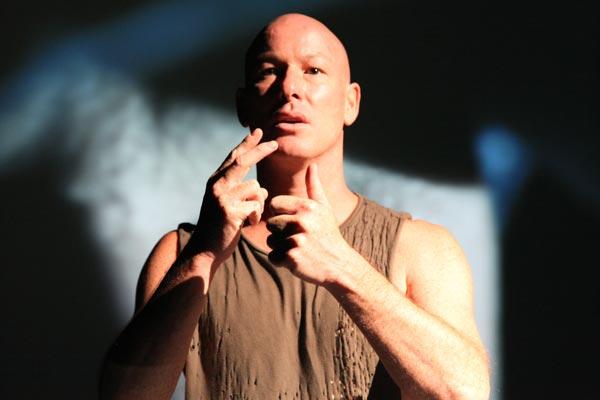

With his Green Room Award-winning production, ‘Blood On The Dance Floor’, which premiered in 2016, Jacob wants to get audiences talking again, not just about the urgent problem of HIV in Indigenous communities, but also about the universal need for love, community, and parental bonding.

Image © Dorine Blaise

‘Blood On The Dance Floor’, directed by Noongar man Isaac Drandic, is a synthesis of styles; Jacob weaves theatre and dance soundtracked by James Henry’s score with cinematically-projected vision by Keith Deverell. The integration of styles, when combined with humour, means the work and its themes are widely accessible, as Jacob explains.

“If you do need to be political or send a serious message, generally it is a lot easier to do that with humour because as soon as you have people comfortable, and they feel safe, then you can have a conversation with people.”

“I didn’t make this as an educational tool but rather as a conversational tool really, but one of the things I do like is after it, I get to talk to people about all the new developments, you know like U=U and PEP and PrEP and all the things that are available to us now.”

By telling his story and speaking his truth across Australia for the last three years, Jacob has provided an outlet for others to talk about theirs after the show, he says.

“I get all kinds of reactions from people that are extremely thankful that I’m putting my story out there and therefore their story is getting heard as well.”

“I’m getting people coming up to me from the Aboriginal community who want to tell me about one of their family members that they’ve lost that they’ve never been able to talk about so there’s a lot of healing done post-show.”

According to Jacob, as an HIV-positive man, he experiences one of two attitudes towards his condition: Silence or worry. As he explains, though, the concern is misplaced.

“When people greet you with that 'aw poor thing' look on their face it’s like, 'don’t be sorry for me, I’m probably healthier than the lot of you, I have to go to the doctor every three to six months to get my bloods tested'.”