Beloved Australian actor and three-time Laurence Olivier Award-winner Philip Quast AM is wrapping up a fulfilling, storied career under the hot spotlight of entertainment, with a stage role in 'Cost Of Living' by Martyna Majok.

Philip is best-known for entertaining masses of '80s and '90s kids in 'Play School', and for a breakthrough theatre role as Javert in 'Les Miserables'. He's also appeared in Royal Shakespeare productions of 'Sunday In The Park With George' and 'Mary Poppins', as well as soap operas like 'Sons And Daughters', 'The Young Doctors' and 'Police Rescue'.

The now 66-year-old grew up on a turkey farm in Tamworth – a far cry from the many stages and studios he's entertained Australians in since. Growing up, his dreams resided in the world of performing rather than the world of poultry.

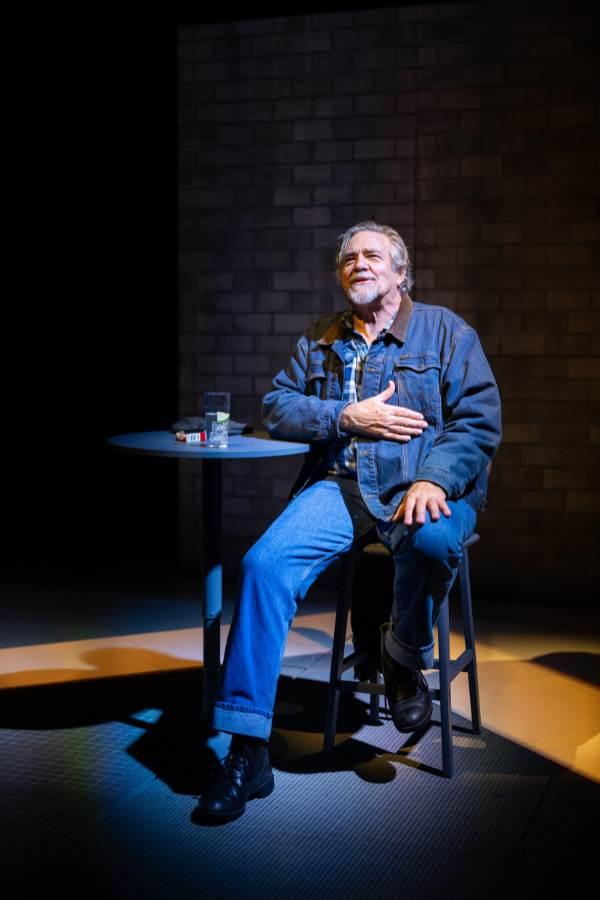

Philip's final role, as Eddie in 'Cost Of Living', holds great power. Eddie is an unemployed truck driver, desperately trying to reconcile with his ex-wife (Kate Hood), who has become a wheelchair user after an accident.

'Cost Of Living' presents raw, emotional conversations around disability – and has become known as the first Australian mainstage production with a 50/50 ratio of disabled and non-disabled cast and creatives. It recently enjoyed a season at Queensland Theatre and will next head to Sydney Theatre Company.

Here, we speak to Philip Quast about his experiences in the entertainment industry, his perspective on where it stands today, his role in 'Cost Of Living', and what's next for him.

First of all, you were a presenter on ‘Play School’ 92 times between 1980 and 1996. . . And you can be heard on the ‘Play School’ theme. Talk a bit about ‘Play School’ and how that opportunity came about/why it interested you.

I really owe the opportunity of doing 'Play School' to Henrietta Clark who is responsible for so much of what 'Play School' became. She saw me in my very first musical 'Candide' for the then Nimrod Theatre directed by John Bell. Henrietta was married to John Clark who was head of NIDA when I trained there as an actor. 'Play School' is probably the most singular educational experience I ever had as an actor, and it instilled in me the need for courage in ‘play’. So much of a person’s education is steeped in fear of failure, 'Play School' always tried to create a space for a child to experience the pleasures of playing and imagining without fear of judgement. An environment where curiosity and fun allow a child to improve simple skills such as listening, singing, counting, rhyming, and role-playing cannot be underestimated. Despite it being done within what seems to be a simple format, it isn’t simplistic at all. The ‘rules’ of moderating a child’s behaviour to allow them to get excited and then settle to listen and watch in turns was always cleverly worked out. Building the synapses to help retain information and to learn ways of extending periods of concentration was always intriguing for me. I learned so much from watching Noni and Benita, from Warren at the piano, working with Tricia, George, Angela, Monica, John, Jenny, Merridy. . . All of them. Included in those 92 episodes were 5 albums plus innumerable live concerts all over Australia. Those concerts helped me to learn the skills an actor needs to gauge an audience because the kids certainly tell you when you’re not being honest.

You’ve also been seen elsewhere on TV and on our stages many times. Can you tell us why the arts were something you felt you were drawn to, especially considering your upbringing on a farm?

I fell into ‘acting’ because it is collaborative. Growing up on a farm in regional NSW required teamwork, even though much of the time you worked alone doing chores. But the better you treated animals the better they behaved and loved you back. They always came first. I think actors achieve more when they concentrate on the task at hand and invest in the other actor more than in themselves. The ‘other actor’ can also be the audience of course. On a farm the environment was the great unknown. Drought, heat, storms etc. I loved nature's uncertainty. Growing up on a farm helped me to always observe everything around me rather than looking inward in a solipsistic way. However, I always felt I lacked a proper education (I went to a ‘one-teacher’ primary school for instance) compared to many of my peers. So, I became an autodidact to compensate and sought out keen minds to inspire me. I‘ve been very lucky to collaborate with some of the greatest directors of the theatre.

Of course, ‘Les Miserables’ is a place many recognise you from. What was the biggest challenge, and on the flipside reward, of playing Javert?

Undeniably the most rewarding part of playing Javert is my friendship with Trevor Nunn who has remained one of my dearest friends for nearly 40 years – I love his mind and his ability to understand human frailty. He is without a doubt the greatest director of Shakespeare in the world and has directed every play Shakespeare wrote. He ran the Royal Shakespeare Company for 18 years, created 'Nicholas Nickleby' and 'Cats'. Cicely Berry always said she owed everything to him for what she learned about the voice and acting. Much of my career has involved playing very flawed and fascinating individuals, which is arguably a big challenge for some actors, the only way to get into their heads is not to judge them in any way but rather to understand them. Trevor encouraged me in this endeavour! 'Les Mis' also led to my forays into the literary classics when I read the book. . . Three times! Including the 250 pages on 'The Battle Of Waterloo'. It inspired me to go back and look at Dickens and The Greeks.

You’ve traversed many landscapes of the entertainment industry in Australia. What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as a creative in the span of your career?

The most important lesson I’ve learned while being an actor is that we are not ‘special people’ — no more than any other artisan or craftsperson or skilled labourer is. It’s a job and the more we leave our own emotions out of what we do the better. It’s the audience's job to feel and not the actors. I feel deprived of my role as a participant if I am being told what to think and feel, I want the challenge of walking away from a night in the theatre troubled and having to do some thinking. I want to have a restless night’s sleep as I am confronted with new arguments, ones that force me to go do some reading and research. Even in shows that are meant to make you laugh and are pure entertainment, I still look for the kernel of ambiguity and conflict for the characters.

Image © Morgan Roberts

On a broader scale, given your knowledge and experience. . . Do you have any commentary on the current state of the arts in this country and where you think it’s headed?

Recently in my theatre visits I’ve experienced a great deal of being lectured at. Too much writing has become proselytising in its nature because there has been a tendency to ‘cancel’ older writers in the lineage. But with that has come the cancelling of craft. OK, much of what has been written is now questionable in its content, but context still must be practiced. If we don’t, we risk throwing many writing skills out with the proverbial bath water. Not to mention understanding how language works, how characters think, and audiences respond to that thinking.

What advice would you give to a young, up-and-coming actor who may well be on the cusp of a huge career in performing?

No advice to a young actor really. . . except. . . Take note of what the mobile phone does to the actor’s brain and deep learning. It’s a lonely life to study, and it requires the discipline to turn off devices for extended periods of time in order to train the brain for a three-hour show of listening and speaking. Stay away from gossip whenever possible, it leads to self-doubt and if you are talking about someone else you know they are talking about you. You can’t practise your craft if you are worrying what people are saying about you. READ. . . It sparks and fires the imagination. Always be pleased for the success of others and don’t take delight in their failures. Smile.

Your ’swan song’ is in Queensland Theatre and Sydney Theatre Company's ‘Cost Of Living’. Why is this the perfect role to wrap things up on?

The years have allowed me to work alongside some of the greatest creatives both here in Australia and across the globe, and I couldn’t think of a more impactful piece of work or talented cast to take my final bow with. It’s a bow I’ll take with such pride. This is a beautiful play! It says something very important about life and love and the need to love. I adore the cast and Pricilla Jackman is a dream. The role of Eddie, like my other characters, is flawed. He is an unemployed trucker and a recovering alcoholic who is trying to patch things up with his wife after leaving her for another woman. Despite this, he is a very loveable character who provides a lot of comic relief in often uncomfortable situations. He isn’t afraid to speak his mind – inclusive of a profanity here and there – and I thoroughly enjoyed bringing him to life onstage at the Bille Brown Theatre (Brisbane) and to be taking him on the road to the Wharf 1 Theatre in Sydney.

It’s a powerful one for disabled and non-disabled creatives. What kind of preparation went into the role for you, and how are audiences responding to it so far?

I always think you learn most, as I have said in these answers, when you don’t lecture an audience. Working with Dan Daw and Kate Hood has taught me lot about disability – not least of all its complexities. Including the challenges facing the aged, the invisibly disabled, those suffering from alcoholism, addiction, and mental health issues. We are too quick to judge and too slow to empathise and tend to look for ways to cast blame for our own troubles which are often borne out of our fears, our laziness, and our lack of curiosity. As a writer Martyna has written a complex play with characters who are all flawed regardless of disability. I know for Kate and Dan that is fulfilling because as actors they are relishing the opportunity to flesh out the three-dimensional nature of their roles. The characters are not just syphers and spokespersons for disability, they are simply people, like all of us, trying to survive as best they can. It's been very humbling and an honour. For people who need to be ‘supported’ in so many ways they give back and teach threefold that of an 'abled' actor. That is a lesson right there. The more you give the more you receive.

Image © Morgan Roberts

How would you describe your working life in the entertainment industry in just a sentence or two?

My career has been an incredible journey. One that’s seen me step into the shoes of diverse, funny, loved and powerful characters. Both on stage and screen, it’s been the diversity of stories I’ve been able to tell and voices I have unearthed that has kept me going.

And what are you most looking forward to once you’ve taken a step back from the stage?

Unfortunately, my wife has had to endure too much of me not being present and being pre-occupied while “I am finishing a hat”, audiences have had ‘more’ of me than my family have. I am most looking forward to having my day and nights stress-free to sit and read, write, and fish. I will still teach occasionally if they want me, and do the odd song here and there, but with a hip replacement and both knees replaced, my body has done enough falling to its knees playing men in despair. My brain feels satiated with enough knowledge of what is required for it to perform. Of course there is always more to learn. But there are other ways rather than being vespertine and shouting at night.

Philip Quast performs in 'Cost Of Living' 18 July-18 August at Wharf 1 Theatre (Sydney).