Josh Belperio's lifetime of written notes will be on full display in the new Under The Microscope show '30,000 Notes'.

Somewhere between a theatre play and a classical music concert, '30,000 Notes' sees Josh taking his audiences through all of the weird and wonderful things he's scribbled down over the years.

As the show progresses, as does its storyline, with Josh musing about finding love, finding who we can love, and how we carry with us those who are no longer here. The show is making its world premiere at Adelaide Fringe.

To expand on the origins of '30,000 Notes' and give us more of an insight into what to expect, Josh sat down to answer a few questions.

First of all, tell us what this show is all about.

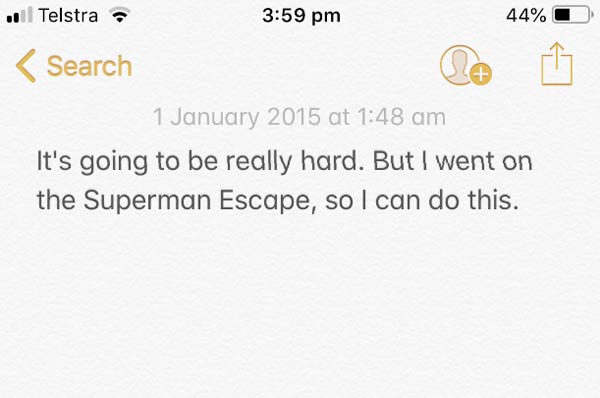

This show is an immersive, indefinable theatrical experience that sits at the intersection of a play, a classical music concert, and a visual art installation. Centred on note-taking, it explores what it means to write anything down, and where our vain attempts to capture the passing moments in our life eventually lead. Framed by a 13-metre wall filled with everything that I have ever written, I (a composer and somewhat pathological hoarder) try and make sense of my musical notes, my post-it notes, my iPhone notes, and everything that I have used to record my past so far, to find what I will carry with me into the future.

Where did the idea for this show originate?

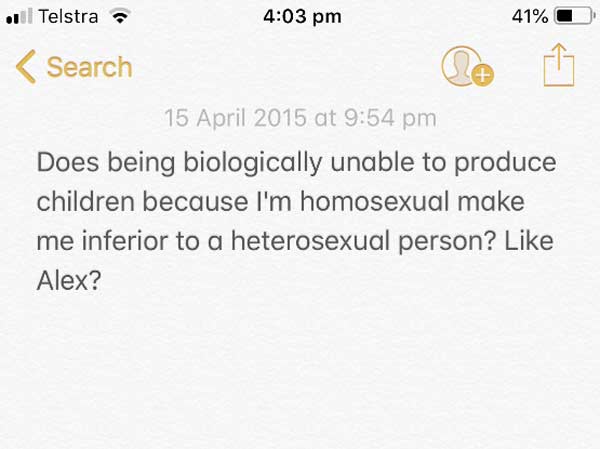

Over the past five years, I have accrued a small oeuvre of choral compositions. They are aspirational pieces, some splitting into up to 20 concurrent parts, which means that their performance requires a lot of resources, and so most of them were just sitting in drawers, unheard and gathering dust. They were composed in response to intensely personal experiences – which were my Nonna’s (grandmother’s) decline and passing from Motor Neurone Disease, and my own coming out and experience of finally finding love. Initially I wanted to present these pieces in a live music concert. But Matthew, my boyfriend and whose love is the subject of the final composition in the show, finds it difficult to connect to classical music concerts. Unlike me, he was not raised in an environment where he was surrounded by classical music, and he is a very visual thinker, so the idea of sitting in an auditorium for an hour without a visual stimulus is not very appealing to him. And, through being in love with someone who thinks so differently to me, I realised that maybe there are other people out there who (shock, horror) do not find the idea of attending a classical music concert appealing. And this is a problem because, as mentioned, the whole score leads up to a musical offering of love to Matthew. I needed to present it in a way that would make him feel that love. And so, Matthew and I brainstormed ways to add visual elements, such as lighting and projection, in order to engage his way of thinking. We decided to contextualise this music in the personal stories that surround it, to give him and people who think like him another avenue to connect with it. And we hope that maybe by making this music accessible to Matthew, we will make it accessible to lots of other people who normally would not attend a classical music concert. And I think this is a promising conjecture, because I am of the belief that film scores and game scores are (for the most part) essentially classical music, and the general public connect with them because they are paired with visuals and story. So that is what we are doing: pairing our music with visuals and a story.

And what have been some of the challenges you've faced in bringing all of these elements together?

Our first challenge (which was also our biggest) was the sheer logistics of presenting a concert with 20 musicians on stage, a complex lighting and set design, and a narrative that I would have to present in between conducting the ensemble. How do you do that, especially on a budget? There are so many challenges involved: the acoustic that you need for a choir is too ‘boomy’ for a one person play, the things that I want to talk about are very intimate and personal, but we would need to do it in a massive auditorium, tickets would have to be very expensive, and the show would be impossible to tour without major financial support – support that we are not in a stage in our careers where we can access it yet. After a lot of thought (and some misgivings about what we have gotten ourselves into!), we realised that the only way to do this is by pre-recording all of the music. That way we can present this story with only one performer onstage, to an intimate audience of 32 people at a time, at an affordable price. But that solution presented another problem: how do you create a show where the hero is the music, without live music?

It's quite the immersive experience and features headphones and a bit of music... Can you elaborate on that?

Sure. So this is the way in which we are hoping to solve the above problem. While the musical purist in me was grumbling about having to give up the live music component, we consulted with a sound designer, who told us about binaural audio.

What is 'binaural audio'?

Binaural audio is this really exciting thing that I’ve only just learned about from our sound designer. It has been called ‘3D sound’, and I would tentatively liken it to the development of perspective in visual art. It is 100% true surround sound. While many speaker systems claim to give you surround sound, and they are getting very impressive and complicated with the addition of more and more speakers, they cannot give you the real experience of surround sound: the sensation of actually being in the room where the sound was recorded. That is what binaural audio allows you do to. In its purest form, it works by putting two microphones in a dummy human head with prosthetic ears. The microphones ‘hear’ the sound just as a real person would hear it, with all of the unique filtering that the shape of the ear does to the sound. When you put on headphones and listen to it, you are listening to exactly what you would be hearing if you were actually in the room where the sound was recorded. It really is remarkable, and you have to hear it to believe it. Instead of the dummy head, we are using regular microphones with a complex signal processing that emulates the dummy head – but the idea is the same. When Matthew and I thought about this, we realised that we can create something that is better than doing a live version, because now we can have these intimate moments when the audience put on headphones, and suddenly the set comes to life with all of this colour and projection, and we get to see my Nonna’s ‘notes’ – which were the home movies that she recorded onto VHS, projected onto the walls – and we’re lifted into this heightened, immersive world, in which we express what we can’t articulate in words.

On the other side of that, can you talk about some of the rewards in preparing the performance?

We have just finished the recording stage of the process – so I have spent the last two weeks conducting a bespoke ensemble of 16 singers and a string quartet. This culminated in recording sessions where we stood in a circle around our microphones and filled this most beautiful chapel in North Adelaide with music. And it was just divine. The ensemble that we assembled, under the mentorship of Carl Crossin (who leads the Adelaide Chamber Singers) has blown my mind. They made my music sound ten times better than I ever thought it could. Add to that our wizard of a sound engineer, Neville Clark of Disk-Edits, and we have a really, really exciting recording that I can’t wait for people to hear.

In terms of the music, what kinds of emotions and thoughts are you hoping to put into the minds of your audience?

Choral music has a long history of being associated with the concept of ‘awe’. The Catholic Church, particularly during the Renaissance, encouraged composers to elicit feelings of awe and rapture from the congregation. This was achieved through the rich, florid polyphonic style, where many voices were layered on top of each other, singing melodies which were independent, yet concurrently occurring. It is a testament to the effectiveness of this music at communicating feelings of bliss and awe, as exemplified by Palestrina, Victoria or Tallis, that 500 years later it captivates me – a gay atheist living in Australia. And choral music is really interesting because it has such a strong association with the Church – and that is part of the core struggle of the show – being the struggle between my queer identity and my Catholic upbringing, the latter of which being instilled in me by my Nonna and her culture. And how choral music, whose sound is still deeply steeped in Christian traditions and ideologies (we had to record it in a chapel, because that’s the only place where this music sounds ‘good’), inspires me, and the multi-layered rich music is a manifestation of my identity, yet I deeply resent extremist Catholicism itself and the ways in which it has wounded me and continues to wound so many members of the queer community. So when my Nonna began to suffer from Motor Neurone Disease, I began to compose music that came to me in the multi-layered forms of Catholic choral music, (filtered by modern harmony, minimalism and even some pop influences), in Latin, with sharp, angular dissonances. And the voices kept on splitting into more and more layers, with more and more dissonance, until there were 20 parts happening at the same time (and when you hear this in binaural audio with all of the voices coming from different directions, it truly is a special experience). I think I was trying to get at something higher than all of this suffering, which Nonna connected to through her faith, but which was closed to me by the loss of mine. Some of that ‘awe’ that is deeper than any religion. This new, dissonant style grew and developed as she got sicker, and as I reconciled myself with my sexuality. When Nonna eventually passed, and the music developed into something more mature – something that celebrates silence and that actually finds a way to make pain and dissonance beautiful. And then the voices all come together again, no longer in multi-layered parts, when we do the love song for Matthew.

And why do you think the show is a good fit for Adelaide Fringe?

The Adelaide Fringe is where you get to see daring and experimental theatre. Theatre that may be a little rough around the edges, often made by artists who are just starting out and beginning to discover their own voice and what they are capable of. I would hope that this show sits in that category. We are definitely not creating something ‘safe’; there is very little that we are doing that is ‘tried and tested’. And the Adelaide Fringe is the place for that, because audiences are willing to take a chance on something new. That is what I love most about the Adelaide Fringe. The process of developing this show has been scary at times, with many moments where we didn’t know if we would be able to pull it off. But all along, we were guided by our wonderful mentors, Carl Crossin, Emily Steel and Andy Packer, and a quote from Stephen Sondheim (who is possibly the closest thing that I have to a religious deity): "You have to work on something that makes you uncertain. Something that makes you doubt yourself... Because it stimulates you to do things you haven’t done before. The whole thing is if you know where you’re going, you’ve gone, as the poet says. And that’s death. That leads to stultified writing and stultified shows … You shouldn’t feel safe. You should feel, 'I don’t know if I can write this'. That’s what I mean by dangerous, and I think that’s a good thing to do. Sacrifice something safe." - Stephen Sondheim, interview with Lin-Manuel Miranda, New York Times, 16 October, 2017.

'30,000 Notes' plays nthspace Adelaide from 19 February-16 March.